Reaching eons into the past, scientific discovery proves once again cats of all types have ruled the world for a long time.

A fossil uncovered in Dawson City, Yukon Territory, Canada, has offered researchers with the University of Copenhagen a further glimpse into one of history’s largest feline predators. The Homotherium latidens, simply known as the scimitar toothed cat, roamed Earth during the Pleistocene Epoch some 2.5 million to 11,000 years ago. With stocky bodies and powerful forelimbs, these epic predators were capable of taking down all manners of larger herd prey like caribou, horses, and bison. The close of Pleistocene Epoch brought the demise of the scimitar-toothed cat and fossils are all that remain to tell us their story.

Image Courtesy of University of Copenhagen

The exact age of the recently-found fossil couldn’t be determined with typical radio-carbon dating methods, meaning the fossil is older than 47,500 years old. And while the age couldn’t be pinpointed, other valuable information about these cats of the past were pulled from the DNA, furthering the image science had already built.

What Does DNA of the Scimitar Toothed Cat Reveal?

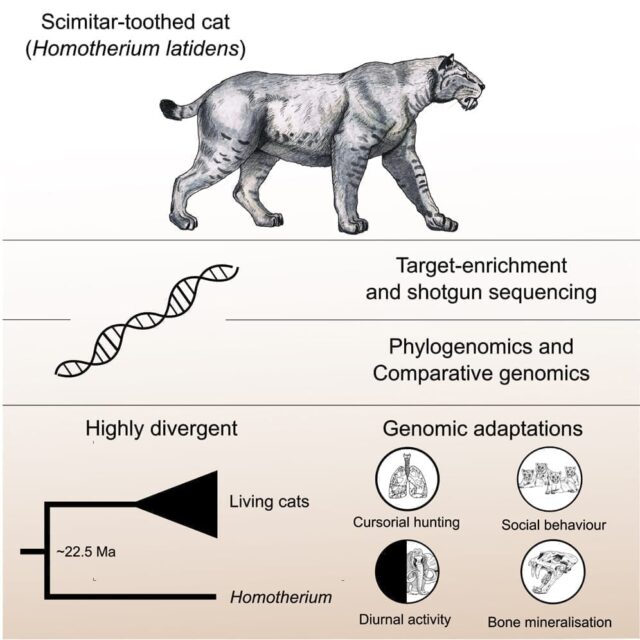

Studies of the DNA extracted from the Homotherium latidens fossil prove the scimitar-toothed cat was a completely different species than other cats living at this time. While a sister species, the scimitar cat was a feline all its own.

Genetic material reveals one physical trait in particular that made them very different than their big cat cousins. The scimitar toothed cat possessed genetic and optic capabilities which allowed for daytime hunting. Most cats living at that time, as well as now, generally hunt at night or the hours nearest to dawn and dusk. But the scimitar cat was running down prey beneath the hot sun.

Image Courtesy of Barnett et al., doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.09.051

The running endurance of the scimitar cat also sets the hunter apart from other felids of the Pleistocene. Cats run in short bursts of speed, but this predator could run impressive distances until either the cat or the prey gave out. Postdoc at the Section for Evolutionary Genomics, GLOBE Institute, University of Copenhagen and co-author of the study, Michael Westbury explained, “They had genetic adaptations for strong bones and cardiovascular and respiratory systems, meaning they were well suited for endurance running. Based on this, we think they hunted in a pack until their prey reached exhaustion with an endurance-based hunting-style during the daylight hours.”

And it seems the world had quite a few of these saber-toothed beasts padding about.

Co-author Ross Barnett said, “This was an extremely successful family of cats. They were present on five continents and roamed the earth for millions of years before going extinct.”

“We Just Missed Them.”

And here’s a thought that might haunt your dreams at night. According to Barnett, “The current geological period is the first time in 40 million years that earth has lacked sabretooth predators. We just missed them.”

Lucky for us! Wild tigers, lions, and cheetahs are wild and well-designed enough without adding worries over their extra-large primitive cousins. Plus, our domesticated kitty-loves give us sass enough to keep us on our toes. Their teeth may be minute replicas of the scimitar toothed cat’s, but they’re still sharp daggers that leave you reaching for the bandages. Every cat parent who’s ever gotten a nip from their darling’s teeth will attest to that.

H/T: www.scitechdaily.com

Feature Image: Image Courtesy of University of Copenhagen